Wood Beads

History of the Wood Beads

THERE surely can be no other item of Scouting regalia more steeped in history, romance, and myth than the famed Wood Badge Beads. Intrinsically, they are practically worthless – two bits of twig on a lace. To those that have won the award however, they are priceless.

Tribal History

As a result of the war of 1879-1880, Zululand, a territory on the west coast of South Africa, north of Durban, had been divided up by the British. (The area is in what was formerly Natal, now known as KwaZulu-Natal.) Each district was ruled by a native chief, with the exception of one that was ruled by an Englishman called John Dunn. The ‘partition’ was not a success. Britain annexed Zululand in 1887, but trouble broke out when Dinizulu, a nephew of the former Chief Cetewayo, led a revolt. The tribes were divided, some for Dinizulu and the others under a coalition led by ‘Chief’ John Dunn.

Chief Dinizulu

General Henry Smyth was the most senior Army Officer in South Africa and Baden-Powell, his nephew, was his adjutant. B-P was sent with a detachment led by Major McKean with John Dunn and 2000 of his Zulus to put down the insurrection and, if possible, to capture Dinizulu.

Chief Cetewayo had been a considerable thorn in the side of the British presence in Zululand a generation previously. By all accounts, Dinizulu, chief of the Usuthu Zulus, was very intelligent. In the British Army Museum in Chelsea, London, there is an exhibit of his writing at the time that he was learning English.

Dinizulu was heavily built man, 2 metres (6 ft. 7 ins.) in height and, on state occasions, he wore a necklace some 3 to 3 ½ metres (10 to 12 feet) in length, consisting of over 1000 beads, ranging in size from tiny emblems to others four inches in length. Dinizulu’s beads, threaded on a rawhide lace, were made of yellow acacia wood, which has a soft pith and formed a small natural nick on each end. (The soft pith dried out or was removed forming a fine hole along the length of the bead – this is perhaps the easiest way to distinguish a Zulu bead from later copies.)

The necklace was considered sacred and was kept in a cave on a high mountain and guarded day and night. It was a distinction conferred on royalty and outstanding warriors; it had been passed down from generation to generation at least from 1825. Charles Rawden Maclean, also known as John Ross, was shipwrecked off the Zululand coast in 1825. He was one of the first white people to meet the great Zulu King Shaka. In his description of the Festival of the First Fruits, he wrote:

“They now commenced ornamenting and decorating their persons with beads and brass ornaments. The most curious part of these decorations consisted of several rows of small pieces of wood … strung together and made into necklaces and bracelets … On enquiry we found that the Zulu warriors set great value on these apparently useless trifles, and that they were orders of merit conferred by Shaka. Each row was the distinguishing mark of some great heroic deed, and the wearer had received them from Shaka’s own hand.”

Maclean was to later meet Dingane, Shaka’s half-brother, who was,

“dressed in the same manner as the king, but without so large a display of beads.”

Baden-Powell later wrote about the campaign to subdue and capture Dinizulu:

“Eventually Dinizulu took refuge in his stronghold, I had been sent forward on a Scouting expedition into his stronghold. He nipped out as we got in. In his haste he left his necklace behind – a very long chain of little wooden beads.”

Modern author Tim Jeal, in his major biography of Baden-Powell, characteristically casts doubts on the ‘official’ version. He points out that B-P did not mention the capture of Dinizulu’s beads in his diary, whereas in a letter dated 1884, now the property of the Boy Scouts of America, B-P mentioned the appropriating of the necklace of a dead African girl. The inference being that B-P’s beads were not Dinizulu’s.

E E Reynolds, in the official Scout Association biography of 1950, has chapter and verse on the dead girl’s necklace, but only the short sentence “B-P became the possessor of the Zulu chief’s necklace” to support B-P’s claim that Gilwell’s beads came from Dinizulu.

What is myth and what is not? I have seen two separate photographs of Dinizulu wearing his beads, one featured above. There is no doubt they existed and were venerated objects. If B-P did not have them, then surely we would have heard of their whereabouts by now. I don’t think that B-P had any knowledge of the way Dinizulu’s ancestor, Shaka, had conferred his beads individually to deserving recipients, but, interestingly, that is exactly what B-P himself chose to do with them.

Scout Use of the Beads

In 1919 at the first Scoutmasters’ training course at Gilwell, B-P had wondered what to give the successful participants, but came up with nothing. Then he thought about the bead necklace. A couple of days later, B-P invited the participants to the restaurant in Scout HQ, presented them with two beads each and told them to go out and buy themselves a shoelace to put them on. Originally he intended that the beads should be worn on the hat.

B-P’s two hat beads

He himself wore two on his hat, the ones are shown here, from the UK Scout Archives, may well be the very hat beads that B-P wore. A Memo exists where he asks his secretary to get “a pair of wood badge beads ‘Camp Chief’ to put on my hat for Thursday!” (Quotation from US Scout Collection Magazine, Scout Memorabilia, November, 1991.)

It seems likely that B-P had got the idea for wearing the beads in his hat after seeing Officers of the US Expeditionary Force in the First World War. Their Stetson hats had a pair of acorns on a thong around the brim that could be tightened to hold the hat in place in windy weather.

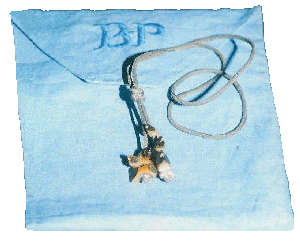

B-P’s Wood Badge pouch

There are pictures of B-P with five beads in his hat, commensurate with the number worn by the first Course Directors in each country to adopt the Wood Badge. According to E E Reynolds in Boy Scout Jubilee the wearing of the beads in the hat was somewhat ‘awkward’, and abandoned in favour of the necklace in the 1920’s. The more likely reason for abandoning hat beads, I feel, is the fact that once you took your hat off indoors, your hard-earned and very prestigious beads were no longer on display!

Shown here is B-P’s own six-bead Wood Badge with a hand-embroidered pouch (was this Olave’s work?) Both artefacts are in the UK Scout Archives.

After world acceptance of Wood Badge training at the 1924 World Conference in Copenhagen. B-P decided to award the first trainer a fifth bead – an original Dinizulu bead.

Sir Percy Everett’s Beads

There is only one other example of a six-bead Wood Badge. B-P presented this to ‘his right hand man’ Sir Percy Everett. Sir Percy wrote later, when he donated his beads to Gilwell:

“These beads are a personal gift from me to the Camp Chief. The Old Chief gave them to me when I was Commissioner for Training in the early days of Gilwell. The time has come when I would like to hand them over as an heirloom. I hope that the [Gilwell] camp chief will wear them and pass them on to his successor.”

John Thurman, Gilwell Camp Chief at the time, first wore the beads when he visited Pennant Hills Training Camp, New South Wales, Australia. The beads were then passed to Bryan Dodgson, the second Director of Leader Training (the first being John Huskins who took over from the Camp Chief John Thurman), then to Derek Twine, Executive Commissioner of Programme and Training and they are now held by Stephen Peck, Director of Programme and Development. (Note the progression of titles of the Chief Leader Trainer.)

The Wood Badge for various sections and ranks

From 1923 to 1925 a small coloured bead was worn above the knot on the necklace. The beads were red, yellow or green and indicated to which section of the Movement the wearer belonged.

The Deputy Camp Chiefs and Akela Leaders were given four beads, of which one was an original Dinizulu bead. Assistant Leader Trainers wore, and still wear, three beads.

Akela Fang

The Wolf Fang, the Akela’s Wood Badge, was introduced in 1922 and went out of use in 1924 or ’25. On another of the Scouting Milestones Pages, on the origins of the Wolf Cubs, there is an image of the Akela Certificate that accompanied this award. Akela trainers wore two teeth. There are known examples of wooden ‘teeth’. The Akela Fang shown here (from the John Ineson Collection) belonged to Hazel Addis, one-time HQ Commissioner for Wolf Cubs and long-term contributor to Scouting magazine.

When the Beads ran out!

At the end of the first Wood Badge course, participants were awarded two of the original beads. B-P invited the winners to attend the Restaurant at Imperial Headquarters, where the awards were presented. Shortly afterwards, it was realised that the beads were a very limited commodity and future winners were presented with only one bead, the recipient being sent into the Gilwell Woods to make a copy of it from fallen twigs.

By 1929 there had been 29 Cub courses, 73 Scout courses, 8 Rover courses and 5 Commissioner courses – a total of 115 courses. If we suppose an average of 25 graduates per course, 2,875 beads would have been needed – and that is if participants only had one – never mind B-P’s six and Sir Percy Everett’s six! There cannot have been half as many beads as that in the original Dinizulu necklace. In fact, some accounts of Dinizulu’s necklace state that the beads graduated from 4″ downward (see the differences in size in the image above of B-P’s six beads), though this is not apparent from the photograph of Dinizulu show

History of the Wood Beads

THERE surely can be no other item of Scouting regalia more steeped in history, romance, and myth than the famed Wood Badge Beads. Intrinsically, they are practically worthless – two bits of twig on a lace. To those that have won the award however, they are priceless.

Tribal History

As a result of the war of 1879-1880, Zululand, a territory on the west coast of South Africa, north of Durban, had been divided up by the British. (The area is in what was formerly Natal, now known as KwaZulu-Natal.) Each district was ruled by a native chief, with the exception of one that was ruled by an Englishman called John Dunn. The ‘partition’ was not a success. Britain annexed Zululand in 1887, but trouble broke out when Dinizulu, a nephew of the former Chief Cetewayo, led a revolt. The tribes were divided, some for Dinizulu and the others under a coalition led by ‘Chief’ John Dunn.

Chief Dinizulu

General Henry Smyth was the most senior Army Officer in South Africa and Baden-Powell, his nephew, was his adjutant. B-P was sent with a detachment led by Major McKean with John Dunn and 2000 of his Zulus to put down the insurrection and, if possible, to capture Dinizulu.

Chief Cetewayo had been a considerable thorn in the side of the British presence in Zululand a generation previously. By all accounts, Dinizulu, chief of the Usuthu Zulus, was very intelligent. In the British Army Museum in Chelsea, London, there is an exhibit of his writing at the time that he was learning English.

Dinizulu was heavily built man, 2 metres (6 ft. 7 ins.) in height and, on state occasions, he wore a necklace some 3 to 3 ½ metres (10 to 12 feet) in length, consisting of over 1000 beads, ranging in size from tiny emblems to others four inches in length. Dinizulu’s beads, threaded on a rawhide lace, were made of yellow acacia wood, which has a soft pith and formed a small natural nick on each end. (The soft pith dried out or was removed forming a fine hole along the length of the bead – this is perhaps the easiest way to distinguish a Zulu bead from later copies.)

The necklace was considered sacred and was kept in a cave on a high mountain and guarded day and night. It was a distinction conferred on royalty and outstanding warriors; it had been passed down from generation to generation at least from 1825. Charles Rawden Maclean, also known as John Ross, was shipwrecked off the Zululand coast in 1825. He was one of the first white people to meet the great Zulu King Shaka. In his description of the Festival of the First Fruits, he wrote:

“They now commenced ornamenting and decorating their persons with beads and brass ornaments. The most curious part of these decorations consisted of several rows of small pieces of wood … strung together and made into necklaces and bracelets … On enquiry we found that the Zulu warriors set great value on these apparently useless trifles, and that they were orders of merit conferred by Shaka. Each row was the distinguishing mark of some great heroic deed, and the wearer had received them from Shaka’s own hand.”

Maclean was to later meet Dingane, Shaka’s half-brother, who was,

“dressed in the same manner as the king, but without so large a display of beads.”

Baden-Powell later wrote about the campaign to subdue and capture Dinizulu:

“Eventually Dinizulu took refuge in his stronghold, I had been sent forward on a Scouting expedition into his stronghold. He nipped out as we got in. In his haste he left his necklace behind – a very long chain of little wooden beads.”

Modern author Tim Jeal, in his major biography of Baden-Powell, characteristically casts doubts on the ‘official’ version. He points out that B-P did not mention the capture of Dinizulu’s beads in his diary, whereas in a letter dated 1884, now the property of the Boy Scouts of America, B-P mentioned the appropriating of the necklace of a dead African girl. The inference being that B-P’s beads were not Dinizulu’s.

E E Reynolds, in the official Scout Association biography of 1950, has chapter and verse on the dead girl’s necklace, but only the short sentence “B-P became the possessor of the Zulu chief’s necklace” to support B-P’s claim that Gilwell’s beads came from Dinizulu.

What is myth and what is not? I have seen two separate photographs of Dinizulu wearing his beads, one featured above. There is no doubt they existed and were venerated objects. If B-P did not have them, then surely we would have heard of their whereabouts by now. I don’t think that B-P had any knowledge of the way Dinizulu’s ancestor, Shaka, had conferred his beads individually to deserving recipients, but, interestingly, that is exactly what B-P himself chose to do with them.

Scout Use of the Beads

In 1919 at the first Scoutmasters’ training course at Gilwell, B-P had wondered what to give the successful participants, but came up with nothing. Then he thought about the bead necklace. A couple of days later, B-P invited the participants to the restaurant in Scout HQ, presented them with two beads each and told them to go out and buy themselves a shoelace to put them on. Originally he intended that the beads should be worn on the hat.

B-P’s two hat beads

He himself wore two on his hat, the ones are shown here, from the UK Scout Archives, may well be the very hat beads that B-P wore. A Memo exists where he asks his secretary to get “a pair of wood badge beads ‘Camp Chief’ to put on my hat for Thursday!” (Quotation from US Scout Collection Magazine, Scout Memorabilia, November, 1991.)

It seems likely that B-P had got the idea for wearing the beads in his hat after seeing Officers of the US Expeditionary Force in the First World War. Their Stetson hats had a pair of acorns on a thong around the brim that could be tightened to hold the hat in place in windy weather.

B-P’s Wood Badge pouch

There are pictures of B-P with five beads in his hat, commensurate with the number worn by the first Course Directors in each country to adopt the Wood Badge. According to E E Reynolds in Boy Scout Jubilee the wearing of the beads in the hat was somewhat ‘awkward’, and abandoned in favour of the necklace in the 1920’s. The more likely reason for abandoning hat beads, I feel, is the fact that once you took your hat off indoors, your hard-earned and very prestigious beads were no longer on display!

Shown here is B-P’s own six-bead Wood Badge with a hand-embroidered pouch (was this Olave’s work?) Both artefacts are in the UK Scout Archives.

After world acceptance of Wood Badge training at the 1924 World Conference in Copenhagen. B-P decided to award the first trainer a fifth bead – an original Dinizulu bead.

Sir Percy Everett’s Beads

There is only one other example of a six-bead Wood Badge. B-P presented this to ‘his right hand man’ Sir Percy Everett. Sir Percy wrote later, when he donated his beads to Gilwell:

“These beads are a personal gift from me to the Camp Chief. The Old Chief gave them to me when I was Commissioner for Training in the early days of Gilwell. The time has come when I would like to hand them over as an heirloom. I hope that the [Gilwell] camp chief will wear them and pass them on to his successor.”

John Thurman, Gilwell Camp Chief at the time, first wore the beads when he visited Pennant Hills Training Camp, New South Wales, Australia. The beads were then passed to Bryan Dodgson, the second Director of Leader Training (the first being John Huskins who took over from the Camp Chief John Thurman), then to Derek Twine, Executive Commissioner of Programme and Training and they are now held by Stephen Peck, Director of Programme and Development. (Note the progression of titles of the Chief Leader Trainer.)

The Wood Badge for various sections and ranks

Three-bead Wood Badge

From 1923 to 1925 a small coloured bead was worn above the knot on the necklace. The beads were red, yellow or green and indicated to which section of the Movement the wearer belonged.

The Deputy Camp Chiefs and Akela Leaders were given four beads, of which one was an original Dinizulu bead. Assistant Leader Trainers wore, and still wear, three beads.

Akela Fang

The Wolf Fang, the Akela’s Wood Badge, was introduced in 1922 and went out of use in 1924 or ’25. On another of the Scouting Milestones Pages, on the origins of the Wolf Cubs, there is an image of the Akela Certificate that accompanied this award. Akela trainers wore two teeth. There are known examples of wooden ‘teeth’. The Akela Fang shown here (from the John Ineson Collection) belonged to Hazel Addis, one-time HQ Commissioner for Wolf Cubs and long-term contributor to Scouting magazine.

When the Beads ran out!

At the end of the first Wood Badge course, participants were awarded two of the original beads. B-P invited the winners to attend the Restaurant at Imperial Headquarters, where the awards were presented. Shortly afterwards, it was realised that the beads were a very limited commodity and future winners were presented with only one bead, the recipient being sent into the Gilwell Woods to make a copy of it from fallen twigs.

By 1929 there had been 29 Cub courses, 73 Scout courses, 8 Rover courses and 5 Commissioner courses – a total of 115 courses. If we suppose an average of 25 graduates per course, 2,875 beads would have been needed – and that is if participants only had one – never mind B-P’s six and Sir Percy Everett’s six! There cannot have been half as many beads as that in the original Dinizulu necklace. In fact, some accounts of Dinizulu’s necklace state that the beads graduated from 4″ downward (see the differences in size in the image above of B-P’s six beads), though this is not apparent from the photograph of Dinizulu shown above. If this gradation in size were the case, there would have been even fewer beads available for B-P’s purpose. The need for replica beads was acknowledged in Scouting for Boys 1926 edition which states “The Badge consists of two facsimiles of the Beads forming the necklace originally belonging to Chief Dinizulu . . . ”

Perhaps the introduction of the Akela Wolf’s fang in 1922 was an attempt at further conservation, and its withdrawal by 1925 was a recognition of the fact that there was no further purpose in conservation, as all of the beads had run out.

When the beads had all been used up, Wood Badge winners might still be lucky enough to be awarded an original if, perhaps through death, some original beads had been returned to the Scout Association.

A Temporary Solution

We have seen that, from Charles Rawden Maclean’s book The Natal Papers of John Ross (quoted above) that bead necklaces were a part of Zulu tradition. Indeed, Baden-Powell himself in his third article for Boys of the Empire on November 17th, 1900, observed how “the slight rattle of a Zulu’s wooden necklet” could help detect the otherwise hidden native at night.

Haydn Dimmock in his Bare Knee Days, published in 1939, delivers a bombshell:

“I discovered [on junk stall in the Portobello Road Street Market in London] a genuine Zulu necklace similar to that which the Chief Scout had secured from Dinizulu, the Zulu Chief. I got the necklace for five shillings and duly presented it to Gilwell Park. It was afterwards broken up and the beads used as [wood] badges.”

In retrospect this might seem something of a deception. Undoubtedly, if these beads were to ever come onto the market, they would erroneously be described as genuine Dinizulu beads and therefore command a high price. On the other hand, I doubt that any lies were told at the time, the ‘sin’ would be that of ‘omission rather than commission’. Would a winner of a Wood Badge rather have been presented with the beads from a genuine old Zulu necklace, or those whittled that year from a Gilwell Beech?

One thing seems certain – the number of original beads, even given the additional necklace, cannot possibly have been enough to have been awarded to the number of people who think that they have one!

World-wide Wood Badge

Five-bead Wood Badge

The Wood Badge very quickly spread throughout the British Empire. Officials of other Scout Associations would come to Gilwell to attend a standard course. They would then often progress to a ‘Trainers Course’, before being appointed as the Chief Leader Trainer in their own country. As the senior ‘Leader Trainer’ they were then entitled to the coveted five-bead Wood Badge. William Hillcourt, ‘Green Bar Bill’, author of Baden-Powell. The Two Lives of a Hero, used an image of his on his letterhead, part of which is shown here. ‘Gilwell Parks’ were set up round the world, sometimes even using the same name.

It is much to Scouting’s credit that there was no bar imposed on those who could attend a Gilwell Course and some of the early participants included Americans. The first Wood Badge course in America however was not run by an American. In 1936 at the Mortimer L Schiff Scout Reservation in New Jersey, a Wood Badge Course was run by the then Gilwell Camp Chief, Colonel Wilson. The participants included ‘the great and the good’ of American Scouting, and many, including William Hillcourt (Green Bar Bill) pronounced themselves ‘inspired’. There was not, however, to be another Wood Badge course in the United States until 1948.

‘Green Bar Bill’ acknowledges that Frank Braden was the driving force behind establishing the Wood Badge course in America in 1948. (Letter in the Dave Scott collection dated March 11th, 1983.)

Variations

There was a point in my researches when I was ready to believe that any combination of beads could be awarded to anybody, so great was the variety of contradictory claims! Below are some otherwise unrecorded occurrences of beads awarded, listed by the official Boy Scout Historian, E E Reynolds, who was on the second Gilwell Wood Badge course and so ought to know:

One bead in a buttonhole for having passed Parts 1 and II

One bead on a hat string for passing the Diploma (i.e. all three parts)

Two Beads on a hat string for the Diploma and for passing special qualifications for becoming a Camp Chief – only to be awarded at Gilwell Park.

(If you have been carefully following the text, you ought now to be able to fill in a test paper asking for the significance of every number ever awarded from 1-6!)

The Zulu Legacy

At the XII World Jamboree at Faragut Park, Idaho, USA, in 1967, on the 60th Anniversary of Scouting, the Boy Scouts of South Africa brought along replicas of the Dinizulu beads. These were made after months of research from Zulus and Rover Scouts in Natal. Four copies were made; one set remained in South Africa, the others were taken to the Jamboree and given to: Jamboree Acting director, R T Lund; the US Chief Scout, Joe Brunton and the first Gilwell Camp Chief, John Thurman.

Replica of Dinizulu’s necklace

Today thousands of Zulu boys are Scouts. In 1987 Chief Minister Mangosuthu Buthelezi of KwaZulu, was the guest-of-honour at a huge Scout rally. Chief Buthelezi’s mother-in-law, Princess Mahoho, was a daughter of Dinizulu. At the rally, the Chief Scout of South Africa, Garnet de la Hunt, took from around his neck a thong on which four original Dinizulu beads were hung, and handed it to Chief Buthelezi, in a symbolic act of returning the beads to their rightful heir.

Currently it is possible to buy a replica’s of Dinizulu’s necklace made of beech at Gilwell Park for a cost of £600. The picture shows part of a ‘Gilwell’ replica necklace, but we know that the beads were not all the same size!

The Wood Badge Training Symbols

AT the 1955 International Conference at Niagara Falls, Canada, the official training symbols were agreed as:

The Wood Badge

The Gilwell Woggle

The Gilwell Scarf – of the 1st Gilwell Park Scout Group

(Note that the famed ‘axe in log’, is conspicuous by its absence from this list.)

The Leather Thong for the Beads

In The Wolf That Never Sleeps – A Story of Baden-Powell, a book aimed at Scout readers, author Marguerite de Beaumont recounts a B-P story of how an old man during the siege of Mafeking came across him at time when he was, very uncharacteristically, ‘down in the dumps’. (Many of his Mafeking contemporaries remember him ‘smiling and whistling under all difficulties’ and he himself, in letters home to his mother, recounts how he sometimes found it very difficult to keep this up, even for the good of the garrison.) The old native gave him a leather thong as good luck token, saying that his mother had given it to him for good luck. Days later, Mafeking was relieved.

n above. If this gradation in size were the case, there would have been even fewer beads available for B-P’s purpose. The need for replica beads was acknowledged in Scouting for Boys 1926 edition which states “The Badge consists of two facsimiles of the Beads forming the necklace originally belonging to Chief Dinizulu . . . “

Perhaps the introduction of the Akela Wolf’s fang in 1922 was an attempt at further conservation, and its withdrawal by 1925 was a recognition of the fact that there was no further purpose in conservation, as all of the beads had run out.

When the beads had all been used up, Wood Badge winners might still be lucky enough to be awarded an original if, perhaps through death, some original beads had been returned to the Scout Association.

A Temporary Solution

We have seen that, from Charles Rawden Maclean’s book The Natal Papers of John Ross (quoted above) that bead necklaces were a part of Zulu tradition. Indeed, Baden-Powell himself in his third article for Boys of the Empire on November 17th, 1900, observed how “the slight rattle of a Zulu’s wooden necklet” could help detect the otherwise hidden native at night.

Haydn Dimmock in his Bare Knee Days, published in 1939, delivers a bombshell:

“I discovered [on junk stall in the Portobello Road Street Market in London] a genuine Zulu necklace similar to that which the Chief Scout had secured from Dinizulu, the Zulu Chief. I got the necklace for five shillings and duly presented it to Gilwell Park. It was afterwards broken up and the beads used as [wood] badges.”

In retrospect this might seem something of a deception. Undoubtedly, if these beads were to ever come onto the market, they would erroneously be described as genuine Dinizulu beads and therefore command a high price. On the other hand, I doubt that any lies were told at the time, the ‘sin’ would be that of ‘omission rather than commission’. Would a winner of a Wood Badge rather have been presented with the beads from a genuine old Zulu necklace, or those whittled that year from a Gilwell Beech?

One thing seems certain – the number of original beads, even given the additional necklace, cannot possibly have been enough to have been awarded to the number of people who think that they have one!

World-wide Wood Badge

The Wood Badge very quickly spread throughout the British Empire. Officials of other Scout Associations would come to Gilwell to attend a standard course. They would then often progress to a ‘Trainers Course’, before being appointed as the Chief Leader Trainer in their own country. As the senior ‘Leader Trainer’ they were then entitled to the coveted five-bead Wood Badge. William Hillcourt, ‘Green Bar Bill’, author of Baden-Powell. The Two Lives of a Hero, used an image of his on his letterhead, part of which is shown here. ‘Gilwell Parks’ were set up round the world, sometimes even using the same name.

It is much to Scouting’s credit that there was no bar imposed on those who could attend a Gilwell Course and some of the early participants included Americans. The first Wood Badge course in America however was not run by an American. In 1936 at the Mortimer L Schiff Scout Reservation in New Jersey, a Wood Badge Course was run by the then Gilwell Camp Chief, Colonel Wilson. The participants included ‘the great and the good’ of American Scouting, and many, including William Hillcourt (Green Bar Bill) pronounced themselves ‘inspired’. There was not, however, to be another Wood Badge course in the United States until 1948.

‘Green Bar Bill’ acknowledges that Frank Braden was the driving force behind establishing the Wood Badge course in America in 1948. (Letter in the Dave Scott collection dated March 11th, 1983.)

Variations

There was a point in my researches when I was ready to believe that any combination of beads could be awarded to anybody, so great was the variety of contradictory claims! Below are some otherwise unrecorded occurrences of beads awarded, listed by the official Boy Scout Historian, E E Reynolds, who was on the second Gilwell Wood Badge course and so ought to know:

- One bead in a buttonhole for having passed Parts 1 and II

- One bead on a hat string for passing the Diploma (i.e. all three parts)

- Two Beads on a hat string for the Diploma and for passing special qualifications for becoming a Camp Chief – only to be awarded at Gilwell Park.

The Zulu Legacy

At the XII World Jamboree at Faragut Park, Idaho, USA, in 1967, on the 60th Anniversary of Scouting, the Boy Scouts of South Africa brought along replicas of the Dinizulu beads. These were made after months of research from Zulus and Rover Scouts in Natal. Four copies were made; one set remained in South Africa, the others were taken to the Jamboree and given to: Jamboree Acting director, R T Lund; the US Chief Scout, Joe Brunton and the first Gilwell Camp Chief, John Thurman.

Replica of Dinizulu’s necklace

Today thousands of Zulu boys are Scouts. In 1987 Chief Minister Mangosuthu Buthelezi of KwaZulu, was the guest-of-honour at a huge Scout rally. Chief Buthelezi’s mother-in-law, Princess Mahoho, was a daughter of Dinizulu. At the rally, the Chief Scout of South Africa, Garnet de la Hunt, took from around his neck a thong on which four original Dinizulu beads were hung, and handed it to Chief Buthelezi, in a symbolic act of returning the beads to their rightful heir.

Currently it is possible to buy a replica’s of Dinizulu’s necklace made of beech at Gilwell Park for a cost of £600. The picture shows part of a ‘Gilwell’ replica necklace, but we know that the beads were not all the same size!

The Wood Badge Training Symbols

AT the 1955 International Conference at Niagara Falls, Canada, the official training symbols were agreed as:

- The Wood Badge

- The Gilwell Woggle

- The Gilwell Scarf – of the 1st Gilwell Park Scout Group

The Leather Thong for the Beads

In The Wolf That Never Sleeps – A Story of Baden-Powell, a book aimed at Scout readers, author Marguerite de Beaumont recounts a B-P story of how an old man during the siege of Mafeking came across him at time when he was, very uncharacteristically, ‘down in the dumps’. (Many of his Mafeking contemporaries remember him ‘smiling and whistling under all difficulties’ and he himself, in letters home to his mother, recounts how he sometimes found it very difficult to keep this up, even for the good of the garrison.) The old native gave him a leather thong as good luck token, saying that his mother had given it to him for good luck. Days later, Mafeking was relieved.